Unbuilt Croton

By Carl Oechsner

Edited by Gretchen Bock

View of Croton with New Croton Dam in background.

View of Croton with New Croton Dam in background.Villages—like people—are born, grow and evolve as time passes. In our personal lives events take place that influence who we are as we move from child to adult. The same with communities—events that take place, or don’t take place, determine the background landscape and character of the community.

Croton waterfront and Upper Village.

Croton waterfront and Upper Village.Following is an overview of sixteen projects whose outcome could have changed Croton-on-Hudson in major ways involving population, architecture, ambiance and character. Read and imagine how Croton might have changed if these projects had been built.

The Sharon-Croton Canal

The Erie Canal, opened in 1825, 363 miles in length.

The Erie Canal, opened in 1825, 363 miles in length.The year was 1822. The construction of canals was a popular undertaking. With the Erie Canal in upstate New York partly finished, everybody was excited about transportation expansion.

Congregational Church, founded 1739, in Sharon, Connecticut.

Congregational Church, founded 1739, in Sharon, Connecticut.One of the projects was a canal from the mouth of the Croton River, up the Croton River Valley to the western boundary of the town of Sharon, Connecticut. The New York state legislature authorized a land survey and estimate of expenses.

One of the 36 locks on the Erie Canal.

One of the 36 locks on the Erie Canal.The new canal would have been heavily influenced by Erie designs with rough stone locks. George Young, the engineer who carried out the first survey, was an associate of John B. Jervis who had started his career on the Erie Canal and would later construct the first Croton dam and aqueduct into New York City.

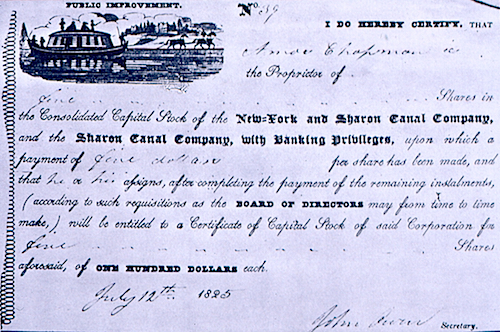

Sharon Canal stock certificate.

Sharon Canal stock certificate.Connecticut was urged to build a similar canal which would link it to the commerce of New England and Canada and make connections with the Erie Canal as well. Stock was sold in what was known as the Sharon and New York Canal Company. Between 1822 and 1829 Connecticut would incorporate five waterways, including the Sharon in 1826.

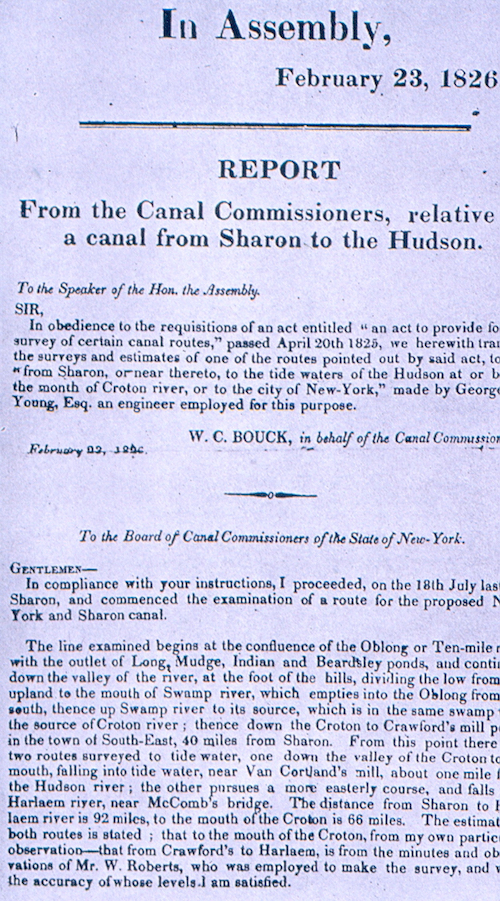

Excerpt from 1826 Canal Commissioners Report.

Excerpt from 1826 Canal Commissioners Report.The preliminary survey stated that the cost from Sharon to the mouth of the Croton River would be $600,000, and a second route moving through Westchester County to the Harlem River in the Bronx, a little over $1,000,000. These sums were for the entire expense of excavation, embankments, aqueducts, locks, bridges and all miscellaneous activity needed to complete the work. Twenty-five to thirty locks were sketched into the plans.

Connecticut’s proposed canal system with Sharon Canal to the left.

Connecticut’s proposed canal system with Sharon Canal to the left.Both states realized that the primary purpose of this long canal would be to tap into the part of New England richest in agriculture and natural resources like iron ore. Eleven furnaces and several forges in the Sharon area could have sent large quantities of iron to New York City.

Handbill on the proposed canal from Sharon to the Hudson River.

Handbill on the proposed canal from Sharon to the Hudson River.The canal involved huge changes for Westchester. Communities on the Croton River would become ports on the waterway. Farm production would be stimulated with easy access to tide water. Village populations would increase. Unfortunately, financial support was inadequate and the engineering problems were great.

Postcard by American photographer Walker Evans ca. 1910.

Postcard by American photographer Walker Evans ca. 1910.New York, therefore, focused its attention on “Clinton’s Ditch” (Erie Canal) to the west, and Connecticut developed various other canal systems. Ultimately the Sharon-Croton River project languished without a spadeful of earth being turned. Investors were left high and dry as the stock certificates became worthless. No canal was ever to disturb the Westchester countryside, including the hamlet of Croton Landing.

Engraving by Ossining artist Robert Havell of first Croton Dam, circa 1842.

Engraving by Ossining artist Robert Havell of first Croton Dam, circa 1842.The chief legacy of the plan was the New York City water supply system. The canal was originally suggested as both a means of transportation and a supply of “pure and wholesome water” for the city. It was the canal company’s activity that directed the New York Water Commissioners’ attention to the Croton River. The canal company failed but the metropolis gained access to Croton water with the completion of the Croton Dam and Aqueduct in 1842.

Postcard of New York Central Railroad.

Postcard of New York Central Railroad.Another reason the canal never materialized was the shrill screech of the first steam locomotive whistle which heralded the coming of a new mode of travel. The railroad could keep inland commerce moving during the winter when the canals were frozen over. In the 1840s, the death knell of the canals was sounded.

Bayreuth-on-the-Hudson

Lillian Nordica

Lillian NordicaMadame Lillian Nordica was America’s first and most glamorous opera singer to attain true international prominence. She became known as a “Yankee Diva”, having sung before presidents, crown heads and working men with equal aplomb. She was born Lillian Bayard Norton in 1857, being named after her sister Lillian who had died at the age of two—a custom of the period called “repeating.”

Both her opera career and private life were exciting. Once a widow under mysterious circumstances, once divorced, married again to a man who wooed her with jewels, she strongly endorsed the fight for women’s suffrage and equal educational opportunities. Nordica’s tragic and untimely death in 1914 came as a result of nothing less dramatic than a shipwreck in the South Seas.

Clifford Burke Harmon, born in Illinois

Clifford Burke Harmon, born in Illinois and reared in Ohio.

Her relationship with Clifford Harmon, a wily self promoter and leading real estate marketer, began in 1907 when Harmon offered to sell to Lillian, and other popular artists, discounted land at his Harmon the New City development on the Hudson River.

In return she agreed to allow her image to be used in a variety of media advertisements for Harmon’s various land development projects. Madame Nordica, as she was known, owned an apartment in Manhattan not far from the Metropolitan Opera House, as well as a county estate in Ardsley-on-Hudson—Villa Amanda, named after her mother.

Villa Amanda estate in Ardsley-on-Hudson, New York.

Villa Amanda estate in Ardsley-on-Hudson, New York.The Ardsley retreat had been built by Cyrus Field for his daughter in the 1860s. Field led the Atlantic Telegraph Company, which laid the first cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.

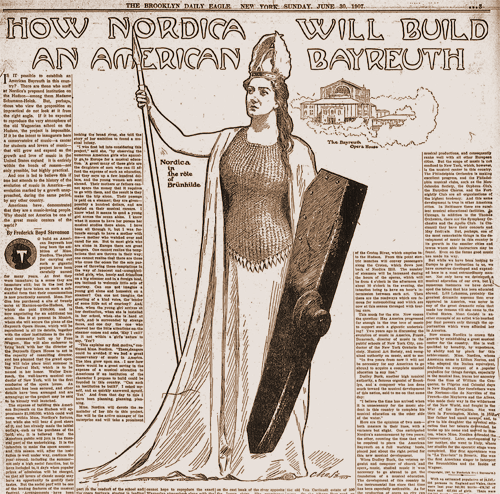

Article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 30, 1907.

Article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 30, 1907.In 1907 Lillian’s cherished dream was to build an opera house, an American Bayreuth at Harmon on the Hudson. The Bayreuth Festival began in Germany in 1876, featuring the operas composed by Richard Wagner in that century. She first appeared at Bayreuth in 1894. “It is my life’s ambition to found in my own country an American Bayreuth. All the years I have been singing, I have dreamed of such an institution,” she said.

Map of Harmon showing proposed American Bayreuth circa 1907.

Map of Harmon showing proposed American Bayreuth circa 1907.So in Harmon she planned to build an Institution of Music with dormitories attached, the buildings to be constructed in a woodland setting. She had bought 20 acres between today’s Old Post Road South and Cleveland Drive, starting from Five Corners up to and including the area across from the Croton Free Library.

Proposed Festival House administration building.

Proposed Festival House administration building.The institute would train women who desired to become Wagnerian opera singers. The Festival House was to be a replica of the Wagner Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, Bavaria, an open air theatre seating an audience of 1,900.

Proposed administration structure, now a private residence.

Proposed administration structure, now a private residence.Management was to be a board of women directors, with an advisory board of men. Twenty-five audience boxes, shaped in a diamond horseshoe, would be subscribed to society figures. The grounds, laid out in a large oval, would provide space on either side of the Festival House for two great venues—a cafe on one side and on the other, a club for donors who supported the theater.

Lillian sailed to Germany in June 1907 and consulted with architects in Munich on the Bayreuth plan at Harmon. Throughout Europe her plan was jeered. The “atmosphere” of Bayreuth could never be transplanted to the Hudson River, critics argued. One said, “Everyone knows that the Hudson is a low, unhealthy river where only malaria and mosquitoes are bred.” Lillian pressed ahead, hiring a music director for the Harmon Festival House, drafting design plans and hoping for the grand opening in 1909.

Book published in 1923,

Book published in 1923, reprinted in 1998.

She returned to New York to learn that her singing contract at the Met had been terminated. In July 1907 she visited Harmon to view the ground- breaking for her new Bayreuth project. Over the next year she would complain that the project was not coming along as fast as she had hoped. Off she went for another European singing tour, followed by concerts in twenty American cities. Coming back to New York, a burning new interest seemed to crowd the Harmon project out of the picture. She had become an ardent suffragette.

Soon it was 1911, Lillian was 54, still singing and hugely popular wherever she appeared. She said, “When my voice finally fails, I will bend my unabated energies to the Great Festival House project to be built not at Harmon, but Cape May, New Jersey.”

It would never become a reality. She died in 1914 while on an Asian tour. The only structure completed in Harmon was an administration building on Alexander Lane at the top of the hill still known as Nordica Hill.

Croton Valley Railroad

1886 Articles of Incorporation.

1886 Articles of Incorporation.In January 1886 articles of incorporation for the organization of the Croton Valley Railway Company were filed in Westchester County. The railroad was proposed to start at the mouth of the Croton River, then run along the river for a distance of eight miles.

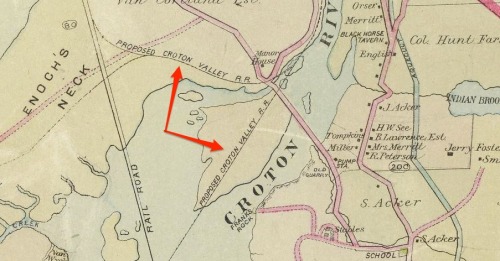

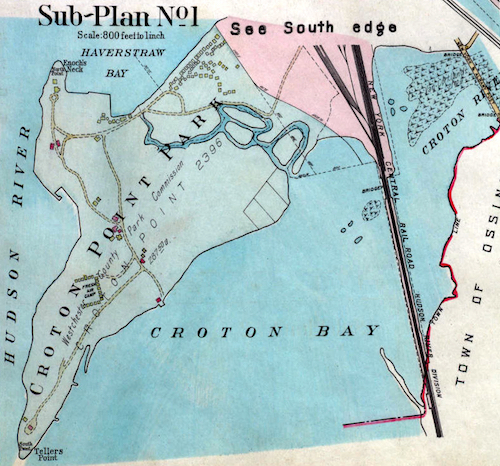

Projected path of Croton Valley Railroad at the the mouth of the Croton River, circa 1891.

Projected path of Croton Valley Railroad at the the mouth of the Croton River, circa 1891.The Railroad Commissioners’ Report for 1890 has the line listed under “Steam Roads not in Operation.” The sum of $18,497.81 was spent on surveying road, and equipment. Eight miles of roadbed had been authorized but none built. Stockholders held a meeting on Wall Street to elect directors and issue bonds for the construction of the roadway. Contracts were signed and work was scheduled to begin. The project was expanded to 23 miles, extending as far as the Connecticut border. Mrs. C.E. Van Cortlandt contracted with the railroad for the right of way along her property on the Croton River.

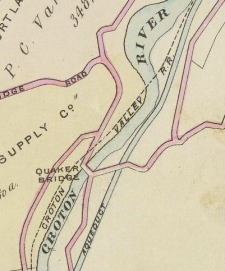

The Croton Valley Railroad would have

The Croton Valley Railroad would have crossed the river near Quaker Bridge.

The 1898 Commissioners’ Report still has the project listed under “Surface Steam Roads not in Operation.” Total monies spent were $22,516.84. Nothing is written about whether any track was laid. A 1904 report states, “Sold under foreclosure to Leila B. Scrymser in 1893. Property has not been redeemed.”

The only other reference to the project is dated September 7, 1906, in a letter from attorney Henry Hesse of Exchange Place in New York City, former president of the Railway Company: “The Company has practically been out of existence for the past 13 years.” The conclusion is that the proposal to construct the new railroad never progressed to being awarded a franchise from the Railroad Commissioners.

Typical Westchester County trolley, this one in Ossining circa 1895.

Typical Westchester County trolley, this one in Ossining circa 1895.Another use for the right-of-way along the Croton River was proposed in 1895. The Croton Valley Electric Railway Company was to construct a narrow gauge street surface railroad—a trolley—four miles long from the New York Central station in the village to the new Cornell [Croton] Dam.

Croton Point Lighthouse

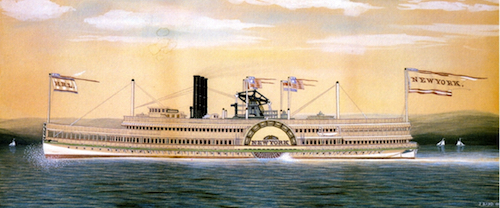

Steamer Mary Powell, “Queen of the Hudson,” built in 1861.

Steamer Mary Powell, “Queen of the Hudson,” built in 1861.In 1846 a group of “masters and owners of vessels and steamboats navigating the Hudson River, of Albany,” filed a petition with the United States House of Representatives, “praying for the erection of a light-house at Teller’s Point, in said river, in Westchester County, and State of New York.” The petition was referred to the Committee on Commerce and on March 3, 1847, an act was passed which authorized the erection of “certain lighthouses.”

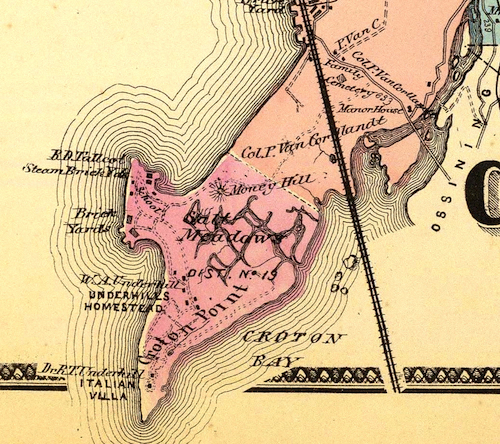

Aerial view of Teller’s Point (today called Croton Point).

Aerial view of Teller’s Point (today called Croton Point).The legislation called for the Secretary of the Treasury to purchase tracts of land within the United States and to “cause said lighthouses to be erected as soon as practicable, and that the following sums be appropriated out of money in the Treasury not otherwise approprioated, for the purpose of constructing said lighthouses.” The act concluded with, “in New York, a lighthouse on Teller’s Point, on the Hudson River, four thousand dollars.”

Steamboat New York plying the Hudson River in 1887.

Steamboat New York plying the Hudson River in 1887.On December 15, 1847, the Treasury Department announced:

“We have directed several superintendents of lights on the Hudson River to proceed with the aid of retired captains of ships and pilots, to select the most suitable sites, and where the site did not belong to the United States, to purchase, at a reasonable rate, a few acres of land for the accommodation of the establishment. In all cases of erecting the buildings, proposals have been invited by advertisement, and the lowest offer accepted. No payment is to be made until the work is satisfactorily done.”

Croton Point, circa 1868.

Croton Point, circa 1868.But on August 14, 1848, the government reported:

“Mr. R.T. Underhill, to whom the land belonged at Teller’s Point, objected strongly to a lighthouse being placed there, alleging that his own dwelling was near the point, and all the land was cultivated as a vineyard and highly improved. He stated that he would not take ten thousand dollars for a site, and begged that all proceedings on the subject should be postponed to give him an opportunity to obtain a repeal of the law.”

River traffic in the Hudson Highlands.

River traffic in the Hudson Highlands.Four months later the government changed their plans:

“Having doubts as to the propriety of erecting a lighthouse on Teller’s Point, we are calling upon the Secretary of the Navy to detail officers to examine several other sites on the Hudson River.”

Tarrytown property owner

Tarrytown property owner Gerald Beekman.

In April of 1849 an act “to change the location of certain light-houses and buoys” was approved and “the light-house to be built on Teller’s Point, on the North river, New York, was transferred to Tarrytown Point, on the same river.

“The appropriation was $4,000. The New York superintendent was directed to purchase the site at a reasonable rate. On consulting the captains and pilots of steamboats, it was learned that the general opinion was that the light, instead of being put upon Tarrytown Point, should be placed upon Beekman’s Point.

Gerald Beekman, the owner of the property, positively declined selling any portion of the point, stating that a light-house would depreciate it for country residences. It is certainly one of the prettiest and most desirable locations on the river, and building lots there will doubtless command a good price. He proposed, however, to sell the government two acres on the extreme point for $3,000. Officials consider it extravagantly high and told him that Congress would not permit so large an expenditure.”

Tarrytown lighthouse circa 1930.

Tarrytown lighthouse circa 1930.Nonetheless, what we call today the Sleepy Hollow Lighthouse—earlier called Tarrytown Lighthouse and Kingsland Point Lighthouse—was installed in 1883. The land and construction cost $21,000.

Over its 78 years of operation, twelve light keepers and their families occupied the five-story structure. The light was automated in the 1950s and operated until 1961, when navigation lights on the Tappan Zee Bridge rendered it obsolete.

In the 1970s Westchester County acquired the building from the Federal Government. In 1979 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Croton Point Dry Dock and Ship Yards

Typical dry dock used for construction, maintenance and repair of ships.

Typical dry dock used for construction, maintenance and repair of ships.On September 6, 1902, the headline in the Croton Journal read, “Big Boom for Croton. Talk of Mammoth Government Dry Dock and Ship Yards there.” The Federal Government was on the verge of purchasing a portion of Croton Point for the construction of large dry docks and a shipyard. A huge channel connecting the main beach with the Hudson River would be constructed, with the entire project employing 1,500 men. The article continued with:

“Croton seems to have been living on these rumors for the past seven months. Where there is so much smoke there may be some fire, and it is hoped that the gigantic enterprise which has been mapped out for us will not end up bringing 1,500 men with their families to Croton. We would then be strictly ‘in it’ with regard to population and many other things. Politically, the Croton vote would then be worth more than a few glasses of beer.”

Harlem-on-the-Hudson

Westchester Park Commission at Croton Point in 1923.

Westchester Park Commission at Croton Point in 1923.In 1923 negotiations by two groups began with the Detroit, Michigan, real estate company that owned Croton Point, a 350 acre property. The first group was the newly formed Westchester Park Commission which visited the area and recommended that the property be purchased and developed into a unique county park providing a range of activities.

Board members of the Hudson River Development Company.

Board members of the Hudson River Development Company.At the same time a number of prominent Harlem investors, calling themselves the Hudson River Development Company, announced that they already had a verbal agreement to buy the land. A letter to the New York Daily News stated, “It is our purpose to make of the Point a very high class place for the enjoyment of our best people.

1923 photograph of Croton Point.

1923 photograph of Croton Point.In view of the fact that we have nowhere to go for amusement where we will feel free from objections and restrictions, Croton Point lends itself for this great movement. We endeavor to make a model of the site in the matter of beauty and conduct. There will be an established community, country club, playgrounds, churches and bathing beaches. We are sure there will be some objections, but on the whole are confident of the favorable opinion and support from the majority of fair minded people in the county.”

Harlem Wall Street Association in 1923.

Harlem Wall Street Association in 1923.An editorial in the Croton-Harmon News stated, “We wish to report the threatened sale of Croton Point to a corporation of Negroes from Harlem. They would take possession of choice tracts and establish a recreation park for colored people only. There has been a great influx of well dressed Negroes from New York City rushing to purchase lots. Anxiety is growing. Land values in our village will depreciate. The county should act quickly to secure the tract for its park system.”

Advertisement for weekend trip from Harlem to Croton Point.

Advertisement for weekend trip from Harlem to Croton Point.

Westchester County Engineer Jay Downer.

Westchester County Engineer Jay Downer.A week later Westchester County exercised the law of eminent domain and purchased the entire piece of land for $360,000. Reaction from the Harlem group was immediate: “It is a great shock and surprise. Anti-Negro sentiment, especially in Peekskill, which is a hotbed of racial feeling, forced the sale to the county. We were going to bring the best element of our race from throughout the metropolitan area to develop an enormous summer resort for colored people.”

County Engineer Jay Downer denied that the purchase was done to block the proposed sale to Negroes. Area newspapers expressed a different view saying, “Officially or not, agitation from nearby residents was given heavy consideration.” For $360,000 Croton Point became a Westchester County public park.

1930 map of Croton Point.

1930 map of Croton Point.In 1926 an international planning conference was held at Croton Point Park where county officials stated:

Croton Point is destined to become one of the greatest inland bathing beaches and recreation centers in the state. To say that parks provide places of recreation is to not give them the credit they deserve. Wherever a park is established, the character of the neighborhood is fixed on a higher plane. It becomes more desirable for residential purposes; home builders and owners are attracted, causing real estate values to rise and taxes to increase. The western and northern sections of the county need a new recreation center. In the near future New York City’s Riverside Drive will be extended as far as the Bear Mountain Bridge.